By Jill K. Cliburn April 8, 2024

A large solar farm in Texas stretches toward the horizon. (Credit: RoschetzkyIstockphoto)

Last fall, Solar Today readers learned about rising opposition to large-scale renewable energy development in communities nationwide. Author Joel Stronberg mentioned groups like the Alliance for Wise Energy Decisions and Citizens for Clear Skies, whose names belie campaigns that promote misinformation and dismiss urgent clean energy goals.1

Stronberg cited a 2023 study from the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law that cataloged nearly 300 renewable energy projects across 45 states that experienced serious organized opposition between March of 2022 and May of 2023 — a 40% increase in such projects compared to the year before.2

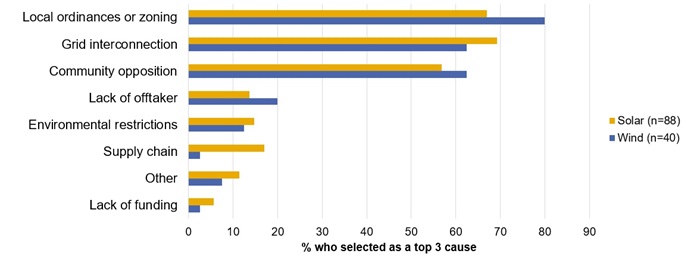

New research confirms the causes of this rising crisis. A survey of solar and wind developers released by Berkeley Lab in January 2024 found that permitting challenges and community opposition closely followed grid-interconnection constraints as the top three reasons for large-scale solar-project cancellations.3 Problems with financing, supply chains and power sales pale by comparison.

The threat that a vocal minority of citizens can pose to solar project approvals and ultimately to U.S. climate goals is real. But efforts to improve permitting processes and to see solar opposition in perspective are also gaining strength, thanks largely to formerly silent citizens who are standing up for solar.

Joanne Scanlon, executive director of the New York–based United Solar Energy Supporters (USES), is one of those formerly silent citizens. Scanlon retired from a career in healthcare and looked forward to spending time with her family before she realized that concern for her grandkids’ future would require her to become a clean energy activist.

She watched opposition building against a proposed 180-MW solar development nearby called the Horseshoe Solar project. She started a Facebook page and then a Nextdoor networking group to offer a different, pro-solar perspective. She started to speak up at public meetings, collaborated with a Sierra Club group, and eventually “plugged into” USES.4

The Horseshoe project was delayed by about five years, but it was finally approved to break ground this year.5

Along the way, Scanlon said, “I learned to ignore personal attacks.” She said it’s important that debate and negotiations take place. That requires bringing well-researched facts to the table.

In this case, landowners’ rights were at stake, but so were the rights and concerns of indigenous people who have long called the region their home. A state review board recommended that a portion of the Horseshoe site be withdrawn from the development plan to protect Native American cultural sites. The developer complied.

On this project and at least a half-dozen more, USES has worked through the permitting process to bring lasting economic and environmental benefits to communities by “harvesting the sun,” according to Scanlon.

She said that USES accepts donations from developers, but that the group’s efforts are not contingent on developers’ support. Pro-solar campaigns do better when relying on volunteers who are known in their communities but not directly associated with the landowners, solar developers or utilities. USES board members and advisors assist frontline volunteers, preparing a trove of informative webinars, referrals and FAQ answers.

That backup crew includes an engineer; a behavioral scientist; a code officer; an energy business consultant and Richard Perez, a solar technology and policy innovator who served multiple terms as a board member of the American Solar Energy Society (ASES).

Perez leads solar research at the State University of New York in Albany. He has been working with his son, Marc Perez, a group manager at Clean Power Research, on ways to meet grid requirements with less battery storage.

The plan hinges on overbuilding and strategically dispatching PV.6 Perez said technical solutions and planning tools for a massive, yet careful PV buildout are at hand. “But the greater challenge today lies in public education,” he said, adding that an educated response to solar disinformation is urgently needed.

In contrast to most local pro-solar groups, those that oppose solar developments are well organized and nationally networked and supported.

At the 2023 ASES national solar conference, I shared my firm’s research on public engagement in a rising controversy around a proposed 100-MW solar-plus-storage project near Santa Fe, New Mexico.7

Using a variety of analytic tools, we reviewed comments that were submitted to county permitting officials during early phases of what turned into a costly and ongoing permitting process. One simple and glaring finding was that just 13% of comments submitted during the first six months favored the project.

Those who opposed the project had quickly organized a mailing list, circulated instructions for writing public comments and op-eds, reached out to newspapers and radio, and launched a website.

Initially, the site was built directly on the website of a solar opposition group in Kansas. Later, the Santa Fe, New Mexico opposition group launched its own website under the name New Mexicans for Responsible Renewable Energy.8

The name echoed that of a national opposition group, Citizens for Responsible Energy, which has been the subject of investigative reporting by National Public Radio (NPR) and others due to its ties to oil and gas interests.9 According to NPR, Citizens for Responsible Energy has ties to similar opposition groups in at least a dozen states.

It would be fair to accept the critique that people of one opinion are simply organizing to counter people of another opinion and that is how democracy works. Yet it is hard to disentangle the subtle disinformation and fears that solar opposition groups have raised.

When you hear “solar,” you think “great,” but there is a dark side. There’s more to the story. Learn how solar contributes to climate change, produces toxic waste, as well as the real economic drivers of the industry. — Citizens for Responsible Solar Website (2024)

One vexing finding from our analysis of comments on the proposed project near Santa Fe, New Mexico was that 52% of those opposed to the project identified themselves as “pro-solar.” According to their websites and comments, project opponents support solar, but only on industrial-zoned land, on brownfields, along highways and on rooftops.

They use specific language to describe how they oppose misplaced “industrial solar” from “corporate solar developers” who make big profits selling to utilities that often intend to “send it” from their backyards to markets far away. Opposition outreach materials often blame “big tech” green tag buyers and server farms for driving solar demand on power markets. This promotes a distorted picture of the nation’s overall clean energy transition.

The potential risks of large-scale solar to wildlife, agriculture and soil health are highlighted in opposition outreach, too, without reference to the perils that wildlife, agriculture and soils already face from climate change and alternative land developments.

In the hands of opposition leaders, the advantages of solar generation — in terms of displacing coal-fired electricity, increasing grid reliability, supporting tax-funded services, leveraging incentives, providing stable income for landowners and jump-starting a solar workforce that also would serve distributed solar — are often cast as unnecessary or uncertain promises.

Despite rapid progress across every aspect of the solar and storage industry, the careful scientists and policymakers that have led our field too often find that fear builds much faster than trust.

For example, the willingness of storage battery partners to share lessons learned about fire safety has become a figurative flashpoint wherever battery storage is part of the plan. The public often misses the fine print about new battery designs, fire prevention standards and emergency response protocols while being drawn to the jaw-dropping visuals from an earlier generation of battery fires.

Social science research has begun to catalog the sources of opposition to large-scale solar and to suggest and test more representative and evidence-based permitting processes. Gilbert Michaud, assistant professor at the School of Environmental Sustainability at Loyola University Chicago and chair of the ASES Policy Division, has been involved in some of that work.

For one recent study, Michaud collected data on proposed projects across six states and oversaw 45 interviews with stakeholders. The study shed light on who was communicating with whom, as well as when and how they were communicating during early development and permitting processes.10

He identified problems and likely ways to fix the system. For example, different media, including social media, should be used to attract a more representative cross-section of participants to both in-person and online meetings.

Outreach and education should begin early. Publicly funded liaison offices in each state could help facilitate local processes. Michaud said he also recommends having technical experts present at all public meetings.

A few of Michaud’s recommendations aligned with process improvements and public education that are already being tested.

For example, Minnesota’s Clean Energy Resource Teams (CERTs) program was already taking this approach. CERTs is a collaboration involving the Minnesota Department of Commerce (the state energy office), the Southwest Regional Development Commission (a representative statewide agency), the nonprofit Great Plains Institute and the University of Minnesota Extension.

CERTs’ mission is to provide education and tools to local communities to support making a rapid and just transition to clean energy. According to Melissa Birch, a CERTs co-director, the program supports large-scale siting processes in three major ways: It provides tools and web-based information tailored to different stakeholders’ needs; it sponsors events, from Farmers Union forums on solar leasing pros and cons to workshops for local government; and it works directly in communities, providing customized research and facilitation.

Predating Michaud’s recommendation, the CERTs team has run local liaison offices throughout the state.

CERTs is focused on building trust, because trust from all parties is key to short- and long-term success. According to Birch, trusted partnerships differ from one rural community to another, but one consistent partner is the cooperative extension service.

“It has been there for over a century and it earned its place as a reliable source of information,” Birch said. “We like to say we are doing clean energy with people, not to people.”

Another resource that CERTs plans to use more is an “energy ambassadors” program. CERTs recognized the trust factor in neighbor-to-neighbor communications, so a year ago, it recruited local energy ambassadors to spread the word about the incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Where siting controversies are brewing, these ambassadors — largely volunteers and often retired professionals — can bring unbiased information about energy technology and the permitting process. They also may act as a conduit if more specialized help is needed. According to Birch, CERTs has more than 800 energy ambassadors signed up.

Getting down to the details of large-scale solar planning is still a challenge, Birch said. In Minnesota, local planning boards generally have authority to rule on conditional-use permits for solar projects under 50 MW.

But the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission now has permitting authority for projects 50 MW and over. Minnesota recently updated its siting guidelines, adding considerations to protect the local environment and culture, but also limiting some demands on developers.

State authority over large-scale solar siting is becoming popular in states that have clean energy and decarbonization goals. State-run processes may address local planning boards’ lack of expertise and time. In some cases, they can resolve issues in the face of conflicting interests.11 As of early 2024, 13 states have exerted some degree of authority over solar permitting.

The response from stakeholders and developers to statewide permitting authorities has been mixed. Some planning boards and local participants resent the takeover of local authority. Developers find that siting criteria increase and permitting costs rise when state authorities get involved, but the faster approvals are welcomed. It is too soon to tell if local tensions and threats of legal action will abate.

In preparing this article, I talked to Dahvi Wilson, who leads a consultancy called Siting Clean.12 Wilson draws on direct experience leading community outreach for a developer, Apex Clean Energy. She shares best practices, while warning that outcomes for any one project remain unpredictable.

For instance, diverse and representative participation is central to democratic processes, but sometimes more vocal solar supporters bring out more intense opponents, and the result is gridlock. A strategy that involves negotiating a benefits agreement for extra monetary compensation or nonmonetary accommodations may help.13

Wilson said she supports using professional facilitators. She also said she favors education and technical assistance for local decision-makers. We agreed that anyone with experience across the solar field or educational background in energy systems could assist. That assistance might be a formal engagement or work behind the scenes or simply sharing personal stories about projects that have worked.

Wilson said, “When you get past all the noise, what you hear is a community asking, ‘What do we really want for our future?’”

Sources

- https://ases.org/nimby/

- http://tinyurl.com/3brx8ru9

- http://tinyurl.com/5brd6b4b

- http://tinyurl.com/5n8e4jdr

- http://tinyurl.com/2s3dfxtp

- http://tinyurl.com/2s58hcv3

- http://tinyurl.com/45sm9p5n

- http://tinyurl.com/bdepyamz

- http://tinyurl.com/2jxmzwzf

- http://tinyurl.com/mr38ph4k

- http://tinyurl.com/ysv2hyem

- http://tinyurl.com/4d8zx4dh

- http://tinyurl.com/3wuxcppz

About the Author

American Solar Energy Society Fellow Jill K. Cliburn has stood up for solar plus storage in her own community. Her website, the Solar Value Project, features work on integrated energy strategies and market analysis for a prompt and equitable energy transition.