By Joel Stronberg July 6, 2022

The U.S. Capitol building serves as the seat of Congress, part of the legislative branch of the federal government. (Source: Wally Gobetz (Creative Commons))

It’s sadly ironic that Joe Biden is unlikely to go down in history as having reigned over a government responsible for finally putting the U.S. — irreversibly — on the path to meet the ambitious climate progress that science demands.

President Biden risked a lot in his adoption and embrace of the most sweeping strategy to combat the climate crisis of any U.S. president in history. Not since the Nixon years, two generations ago, have federal policymakers been asked to consider so sweeping a series of environmental protections.

The good works of those years included the Clean Air and Water Acts, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Council on Environmental Quality. They continue a half-century later to serve as the foundation for federal environmental-protection and clean energy policies.

It was a time when a divided government — a Republican president and Democratic Congress — could still work together to achieve critical ends. Then it was a time when rivers burned, and now the planet boils. Where’s the constituent outrage, I wonder?

Notwithstanding the Democrats’ titular control of the House and Senate, President Biden has met stiff opposition to his aggressive climate change agenda. The most damning resistance has come from within his own party.

It’s not the first time a Democratic Congress and president failed to enact federal programs and policies with the heft necessary to confront the climate crisis.

The last time the Democrats controlled both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue was from 2009 to 2011 (the 111th Congress). Barack Obama led the nation, Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) was the Speaker of the House, and Harry Reid (R-NV) held sway over the Senate as majority leader.

In 2009, the House narrowly passed the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009. Speaker Pelosi heralded the bill as transformational climate legislation. The House vote, largely along party lines, was 219-212.

The 1,200-page omnibus bill mandated a 17% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 and an 83% cut by 2050. The legislation put a price on carbon dioxide through a cap-and-trade system to meet the mandated reductions. It further required that 20% of electricity was to come from renewable sources and increased energy efficiency.

Neither the full bill nor a stripped-down version ever made it to the Senate floor for a vote. Had it been brought to the floor, it would have been filibustered by the Republicans — with more than a few Democrats relieved over never publicly having to vote “No.”

The more things change, the more they seem to stay the same.

In 2010, Joe Manchin was the Democratic governor of West Virginia and gunning to succeed the late Robert Byrd. To show the voters of West Virginia where he stood on the bill, he filmed a campaign ad in which he fired a rifle at a copy of the legislation.

Senator Manchin is still shooting down comprehensive federal climate policy a dozen years later. These days he has twin barrels. As the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee chair and the 50th Democratic vote in an equally divided chamber, he is now the most powerful politician on Capitol Hill on climate matters.

The one piece of climate-related legislation that can be relied on is the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act popularly known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework. How climate-friendly the infrastructure projects paid for under the Act are largely depends upon the states.

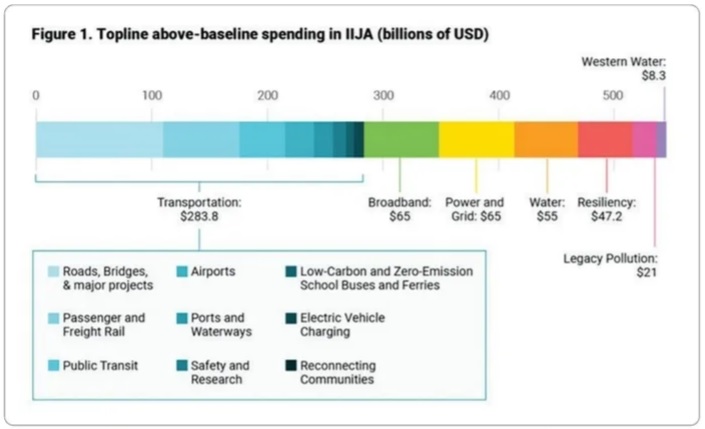

The legislation provides $550 billion in new federal dollars to build a resilient and sustainable infrastructure. Including redirected funds already in agency budgets, the IIJA carries a price tag of nearly $1.2 trillion.

BIF is far from the sweeping climate legislation considered by the 111th Congress — further still from Biden’s proposed progressive agenda. The bill focuses on electric transportation, clean water and rural broadband.

IIJA looks to support domestic manufacturing to reduce reliance on Chinese parts and products such as semiconductors. It provides badly needed dollars to fix bridges, repave highways, build new on- and off-ramps, electrify public transit systems and create charging stations for electric vehicles.

It’s a lot to ask of $550 billion. It’s even a lot to ask of 1.2 trillion; see Figure 1.

The transportation/clean water/broadband focus can be misleading. Under the Act’s provisions, there are ample opportunities to apply solar and other clean energy, energy efficiency and storage technologies.

Climate-related projects might include powering airports, ports and waterway facilities with solar and wind. The same goes for installing solar power on school buildings, adding panels to electric school buses, and creating workforce-development programs in high schools and junior colleges.

Fair warning: the 2,000-page bill is not for the faint of heart. Much of the funding will go through existing programs such as the Secure Rural Schools program that’s under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Forest Service. The White House has published a 465-page guidebook identifying the various programs, dollars, and agencies receiving and disbursing IIJA dollars. There’s resistance at the state level for using the available IIJA funds for clean energy and energy efficiency. On Jan. 19, 16 Republican governors sent a letter to president Biden urging him and senior adviser and infrastructure coordinator Mitch Landrieu to “[not] attempt to push a social agenda through hard infrastructure investments.”

It’s unfortunate that the hyper-partisanship that plagues Washington may also keep states from using available funds with an eye to climate resilience and adaptation, as well as more traditional concrete and steel projects.

It need not happen that way. It’s up to the climate and clean energy communities to engage with state decisionmakers about the choices they’ll be making over the months and years that IIJA funding will be available. Fortifying communities for future climate-related disasters is only good planning.

About the Author

Joel B. Stronberg, MA, JD is the president of The JBS Group/Civil Notion. He’s been analyzing and advocating federal and state policies on behalf of clients for over 40 years. These days, his portfolio of activities also includes being a columnist at illuminem.com, a featured voice at Resilience.org and Energy Central, and a speaker at meetings and on podcasts.