By Akua Debrah and Luke Danielson September 22, 2023

Figure 1. This cobalt was cleaned and sorted to be bagged and tagged for buyers in Kamilombe in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Credit: Emmanuel Umpula, Afrewatch)

The COVID-19 pandemic focused attention on the importance of supply chains. One of the key supply chains was in the battery-metals industry.1

There are real and significant problems in the supply chain of cobalt, a critical battery mineral. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which is one of the world’s poorest nations, produces about 70% of the world’s cobalt. Close to 10–30% of this cobalt comes from artisanal miners, mostly operating illegally. Some of them are children, often in abusive labor conditions. These miners typically have little to no training or protective gear.2

The DRC’s cobalt is critical to achieving the energy transition’s pathway of limiting global temperature increase to below 2°C (or at 1.5°C) by 2050.3 To hasten the transition, the world wants products that can be made greener through rechargeable battery technologies. Battery storage, together with renewable energy like wind, solar, bioenergy, etc., is key to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement.4

Demand Implications and Significance of Cobalt

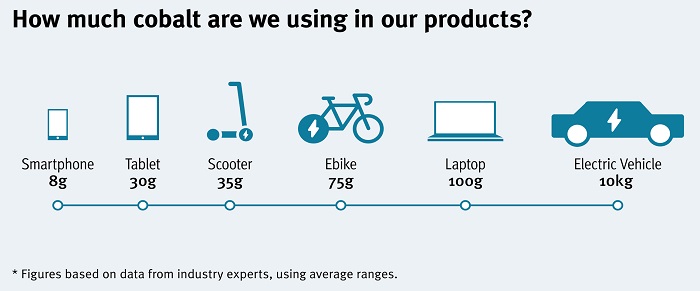

Electronic goods and electric vehicles (EVs) that use rechargeable batteries are often engineered with lithium-ion (Li-ion) to extend the life cycle of these products. Most cell phones, computers, cordless electronics and EVs use Li-ion batteries and often have cobalt in their makeup (see Figure 2).

https://www.raid-uk.org)

Cobalt provides batteries with thermal stability, longevity, range and high energy density. It is very useful in enhancing the rate at which batteries can be charged and discharged. There are at this stage few known substitutes. Aside from batteries, it is used in alloys and superalloys in gas turbines, aircraft manufacturing, cemented carbides and modern medicine. It is also used as a catalyst in the petrochemical industry.

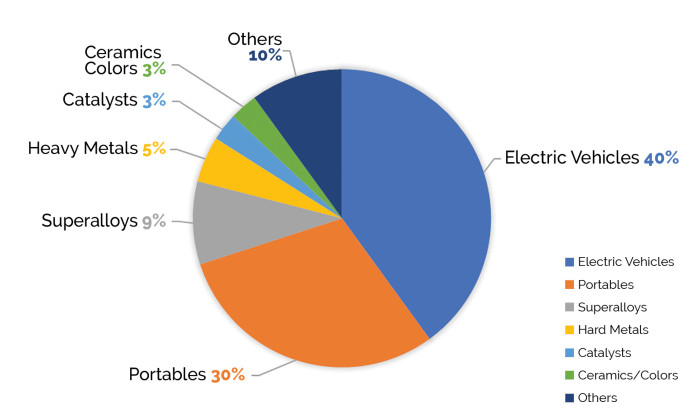

According to the Cobalt Institute and S&P Global, world demand for cobalt will quadruple by 2030, driven by its use in portable electronics and EVs, some of which is taking place to meet growing climate change concerns (see Figure 3).5 These two major industries have the highest demand for refined cobalt.

Overall, the demand for green mobility is expected to increase the demand of Li-ion cobalt options despite an alternative battery makeup that relies on lithium, iron and phosphate (LFP) currently comprising about 30% of all EVs sold.6 It is anticipated that cobalt demand will remain strong and may outstrip supply by 2030, pushing prices upward.7

Green Minerals and Cobalt: Will There Be Enough for the Transition?

The switch to EVs can translate to lower emissions and reduced carbon footprints. But many students of the energy transition point to the significant cost to the environment and the behemoth investments that will be required.8

Nico Valckx and his colleagues at the International Monetary Fund argue that the quantum and cost of the materials for this transition are colossal, requiring about 3 billion tons of metals.9 Beyond cobalt, today a typical EV battery pack consists of 25 pounds of lithium; 60 pounds of nickel; 44 pounds of manganese; 200 pounds of copper; and 400 pounds of aluminum, steel and plastic.10

Many green energy systems, such as solar, wind, etc., require larger quantities of copper, silicon, silver, zinc, iron ore, cobalt, magnesium and aluminum, as well as other materials. The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) recent roadmap for net zero by 2050 highlights supply shortages of these minerals, such as lithium, nickel, cobalt and vanadium, in relation to available demand.11

We anticipate an unprecedented shift toward green mobility, which will further heighten cobalt demand. General Motors is investing $6.6 billion in EV plants with the aim to convert 50% of its North American capacity by 2030.12 Ford Motor Company has followed suit. EVAdoption, a consulting and advisory firm, forecasts that EV and plug-in hybrid sales will rise to about 29.5% domestically by 2030 from a mere 3.4% in 2021.13

China, the European Union, the United States and others are competing mightily to overcome supply chain constraints in an industry that is likely to be a determinant in national security and economic leadership in coming years. It is not clear that current measures will produce enough of the necessary minerals, including cobalt, in view of the IEA report and others with similar conclusions.14

In this fight for control of resources, the DRC is home to half of the world’s known cobalt resources and currently accounts for around 70% of global production. It is a country with weak internal governance and regional factionalism. This is the troubled arena in which the geopolitical conflict over cobalt is playing out.

The DRC and Sourcing Challenges

The DRC is a poor country, ranking 175th of 189 countries in the United Nations Human Development Index. It has suffered greatly from foreign interference, internal division and weak governance. The country has not recovered from the Second Congo War of 1998-2003, in which 5.4 million people died, the world’s deadliest conflict since World War II.15

Resources from the DRC have long fueled the world’s industrialization and major world wars, from timber and rubber during the era of King Leopold II to uranium for the development of atomic bombs and currently to cobalt for the technologies of our modern world.

Most artisanal miners, or “creuseurs” as they are commonly called in the DRC, dig for cobalt in shaft-like holes that can range from between 3 and 50 meters deep with no support beams or mechanized equipment for descent in the mines. Their means of sustenance and livelihood are dependent on whether they can extract enough ore from these sites to sell. Their income is often under $13 per day.16

Every day is a death trap waiting to steal a life in illegal cobalt-mining sites. Beside the unsafe excavated pits, villages that sprout around some large-scale mines carve out a living through scavenging the mine tailings (or waste) for cobalt ore to make ends meet.

In most cases, even a hard day’s work fails to produce enough ore. Many illegal mining families go to bed hungry. Women feature prominently in the value chain, with no protective gear, while being directly exposed to cobalt dust, which has been noted to cause many respiratory diseases, including lung disease. This dust has also been linked to cancers of adults and birth defects of children born in these communities.17, 18

At some point, the world turned against ‘blood diamonds.’ It may for similar reasons turn against cobalt produced by these deeply troubling means. Some may feel that so long as consumers in rich countries get products they like, there is no limit on what consumers who buy these items will accept.19

But some consumers appear to be demanding more accountability and ethically sourced raw materials. Buyers who are not approaching their sources of supply responsibly are subject to growing supply chain risks. These include uncertainty of cobalt’s availability, lack of physical security, fluctuations in the cost/price of cobalt, and the environmental and human costs of artisanally-sourced cobalt.20

Challenges to DRC internal governance; conflicts between the DRC and some of its neighbors; and external pressures among France, Russia, China and other interests to control the nation’s mineral assets all result in unstable conditions. The threat to the availability of cobalt is hard to mitigate in an environment where mineral assets are highly politicized and often used as bargaining chips to win the next election.

These social and human costs and the resulting environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk factors can retard the energy transition. This has become highly problematic for companies that want to ensure that their materials are responsibly sourced and that their supply chains are free of violence, forced labor, child labor, unacceptable environmental practices, illegal labor and human rights violations.

This has been very difficult to achieve. The largest producer of refined cobalt, Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Co., Ltd., sources directly from Congo Dong Fang International Mining (CDM) and sells to manufacturers in China and South Korea that resell to big corporations such as Apple and Samsung, among others.21

CDM and other mining companies still source from uncertain middlemen and artisanal cobalt producers, according to the Harvard researcher Siddharth Kara.22 The cobalt artisanal miners produce is often sold onsite to middlemen who then sell to representatives of industrial cobalt-mining companies, where it is mixed with what these mines produce themselves, thus tainting the supply chain.

Several approaches have been suggested. The DRC government’s approach has been to create something called the Entreprise Générale du Cobalt (EGC) to address ethical concerns of cobalt supply chains.23 But it is not clear how well this is working. The EGC has not been fully implemented since its establishment in 2019.

On the international front, voluntary private-sector initiatives have been in the works for some time (albeit on a pilot scale). These include the Global ASM Cobalt Framework Vision spearheaded by the Cobalt Action Partnership, the Responsible Cobalt Initiative and the Fair Cobalt Alliance (FCA). These have the goal of implementing ESG guidelines for artisanally-sourced cobalt. But we are far from where we need to be.

There are suggestions to boycott cobalt supply from the DRC entirely or to use cobalt-free alternatives such as LFP.24 But this would dry up one of the few revenue streams that help the DRC survive.

Alternative sources of cobalt are few and will take years to develop. And cobalt-free alternatives are still not at par with cobalt options. Range, performance and charging time remain key issues for most potential EV buyers. The need for the energy transition is now, not years in the future when these options may be more viable.

Can the Energy Transition Be Green?

We, as a world, need practical and concerted efforts to support a better outcome for the DRC and its inhabitants while assuring responsible cobalt supply chains. Coalitions with broader stakeholder engagement and concerted action from consumers, businesses and the DRC government about responsible and safer forms of illegal mining and elimination of child labor would be a start.

A few steps are already in the works, such as the Global Battery Alliance and the FCA. Programs and strategies to certify clean cobalt through formalizing the informal cobalt mining sector will assist in making mines and workers safer.

Recycling is also an option to augment supply constraints. But it remains costly, and the technologies are still in early development. Apple is a trailblazer in this regard, since it currently recycles 25% of the cobalt from its phones and has set a target of 100% recycled cobalt from all iPhones by 2025. There is the need for economic, regulatory and non-market strategies to be directed toward cobalt recycling.25

There are also domestic U.S. programs such as Manufacturing Capability Expansion and Investment Prioritization under the U.S. Defense Production Act Title III to support Jervois Global Ltd.’s Idaho cobalt operations.26 This will assist in developing the nation’s cobalt-nickel assets and expand supply if feasible. Furthermore, the act will assist mining companies to access about $750 million to boost domestic critical-minerals production.27

But what is expected to be produced in Idaho is minuscule compared to what the DRC currently produces. Developing new mine assets usually takes at least 4-12 years for greenfield sites and up to five years or more to expand brownfields.28 There will therefore be a domestic deficit for at least 5-10 years that can only be supplemented by establishing more reliable and responsible cobalt supply chains.

We need reliable and transparent certification systems for the cobalt entering the market. The global community has ignored the problems of the DRC for many years. Possibly, tainted cobalt is what will get the world to start taking these problems and their resolution more seriously. That will happen when consumers start asking blunt questions of sellers about where the cobalt in their batteries originates.

Sources

- https://tinyurl.com/4c3h7f69

- https://tinyurl.com/mrx9jjke

- https://tinyurl.com/3fkw62sa

- https://tinyurl.com/269w2e5n

- https://tinyurl.com/2kt6duef

- https://tinyurl.com/3ya94bhw

- https://tinyurl.com/bdxdjzxx

- https://tinyurl.com/2p5udxcv

- https://tinyurl.com/4a4w95nb

- https://tinyurl.com/2fm8vn4c

- https://tinyurl.com/6rsask84

- https://tinyurl.com/vekkrxxf

- https://tinyurl.com/42rx45na

- https://tinyurl.com/4a4w95nb

- https://tinyurl.com/2bs4b3e8

- https://tinyurl.com/yc2xs36u

- https://tinyurl.com/2wrawzte

- https://tinyurl.com/bdambary

- https://tinyurl.com/286zwc33

- https://tinyurl.com/ysf8jcdt

- https://tinyurl.com/4m3b9am8

- Ibid.

- https://tinyurl.com/bdzka3h5

- https://tinyurl.com/2f2vd554

- https://tinyurl.com/4d7y8n9a

- https://tinyurl.com/ukacsmpf

- https://tinyurl.com/ytwb6tzx

- https://tinyurl.com/z43jwn4b

About the Authors

Akua Debrah is a minerals policy and energy expert and a consultant at Sustainable Development Strategies Group (SDSG). She was a research associate and fellow with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization and its Economic Commission for Africa. She is a visiting lecturer at the Wits Mining Institute in South Africa.

Luke Danielson is the president of SDSG, a nonprofit research institution. He was director of the Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development Project. He has been a faculty member at several universities and was inducted into the International Mining Technology Hall of Fame. He is a former American Solar Energy Society member.