By Jenna Tatum, Director, Building Electrification Institute September 24, 2021

The Kiowa County Commons building in Greensburg, Kansas, a LEED-Platinum designed building with 33 solar panels that produce 4.6kW of power, uses heat pumps for efficient electric space heating and cooling. Credit: ©Joah Bussert, NREL © Joah Bussert, NREL

Across the U.S., a growing number of cities have committed to ambitious climate goals to help avert the worst impacts of climate change and demonstrate successful models for action. Many of these cities have begun efforts to transition buildings away from fossil fuels and toward high-efficiency electric options that can use increasingly clean and renewable power. The experiences of these cities can help inform the efforts of other local governments, as well as approaches at the state, regional, and federal levels of government, whose efforts will eventually be required to transition the entire U.S. economy off fossil fuels.

The Problem

Today there are over 70 million homes and businesses in the U.S. that burn fossil fuels, including natural gas, oil, or propane, to provide space heating, cooking, and hot water. This on-site fossil fuel combustion currently makes up the majority of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from buildings in the U.S.1 In some North American cities, on-site building fossil fuel use can account for the largest source of citywide GHG emissions, particularly in heating-dominated climates like those in the Northeast.2

Cities have found that to meet their ambitious climate goals, reducing GHG emissions from the building sector will require more than basic energy efficiency measures. Instead, it will require transitioning building systems completely away from fossil fuels and toward options that can use renewable energy. While recent innovations in electric generation and transportation are driving down emissions in these sectors, the building heating and cooling industry has remained largely unchanged for decades, and building-based GHG reductions are lagging. New policy innovations are needed to accelerate the transition of buildings away from fossil fuels and toward clean energy.

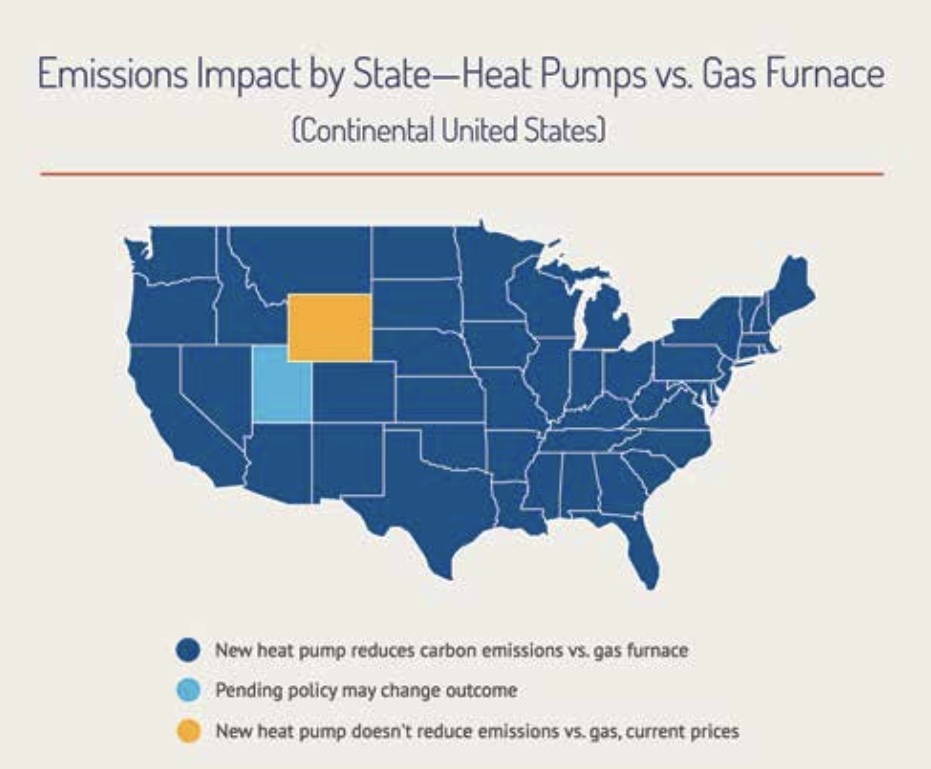

According to a recent analysis by RMI, installing heat pumps today reduces GHG emissions versus gas heating systems in states representing 99% of the U.S. population. © infogram.com

New approaches are also needed to ensure that this transition is equitable and does not worsen the current equity and affordability crises in the U.S. Without thoughtful planning, well-meaning policies to transition buildings off fossil fuels could result in unintended harm. Cities, in particular, are on the front lines, as the populations of many cities have increased rapidly in recent years, but their housing supply has not kept pace with this demand, and incomes have stagnated despite a staggering rise in housing costs and other expenses. Many cities are now facing an increasingly severe crisis of affordability. In New York City, for example, rents increased by nearly 60% between 2012 and 2020; in San José, rents nearly doubled in the same period.3 In 95% of U.S. counties, a minimum wage worker is now unable to afford a one-bedroom rental.4 Moreover, the economic impacts of COVID-19 have deepened existing inequities, causing millions of job losses and threatening evictions and homelessness for thousands of Americans.

The Solution

The most viable option to move buildings away from fossil fuels today is to convert their heating and cooling systems to high-efficiency electric air source heat pumps (ASHPs) and heat pump water heaters (HPWHs). These technologies use a compressor to pump heat from the outdoor air to provide indoor space heat or hot water. Because these technologies are so energy efficient, heat pumps reduce emissions in most parts of North America today, and have the potential to dramatically reduce emissions over the long term by using increasingly clean electricity powered by renewable sources.5

Converting buildings to heat pumps can also provide health, safety, resiliency, and cost-saving benefits to communities, and with intentional planning, these benefits can be delivered first to those who need them most. During warmer seasons, ASHPs can provide cooling (in addition to heating), which is a growing need as cities across North America experience increased heat and heatwaves due to climate change. Low-income communities and communities of color face disproportionate health impacts from higher temperatures and heat waves because they tend to live in areas with higher “urban heat island” effects and are more likely to lack air conditioning in their homes.6

Converting away from fossil fuels in buildings will also help reduce both indoor and outdoor air pollution. Air pollution also disproportionately impacts low-income communities and communities of color, who in the U.S. are exposed to 30% higher levels of pollution than wealthier white communities.7 Outdoors, nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions from fossil fuel appliances in buildings often contribute far more emissions than power plants in many states.8 Dangerous levels of air pollutants have also been found indoors, which has been linked to gas appliances including gas stoves and wall furnaces, and the impacts are worst in smaller homes where low-income residents are more likely to live.9

Moreover, electrifying building systems will also improve public safety by reducing the risks of fire and deadly gas explosions, such as those experienced in San Bruno, California and Lawrence, Massachusetts in recent years.10,11

Building electrification also has the potential to reduce housing and energy costs, although the local climate and utility rates will affect the outcomes. That said, all-electric new construction is lower cost to build than mixed fuel construction for most types of buildings, which is why more than 40 California cities have already enacted all-electric requirements for new buildings, and dozens of additional cities around the country are doing the same.

Retrofitting oil, propane, and electric resistance heating systems to heat pumps will also reduce energy costs in most cases. Retrofitting gas systems can reduce energy costs in many cases, especially when paired with weatherization and other envelope improvement measures. Still, the upfront costs of electrification retrofits can be high, and public investments will be needed to ensure these costs are not passed on to low-income renters and others who can least afford them.

Realizing an equitable transformation across millions of buildings will be an enormous challenge, but we cannot allow the challenges we face to halt our efforts to avert climate disaster and equitable electrify our buildings. The good news is that cities are already leading the way in developing and implementing policies and strategies to scale up building electrification and to prioritize benefits for those who currently suffer disproportionate housing, economic, and health burdens.

About BEI and Our Cities

The Building Electrification Institute (BEI) envisions a world where we no longer burn fossil fuels in our buildings, and as a result, we will have cleaner air, safer and more affordable housing, and healthier, more livable communities.

BEI Cities

With this transition, it is also possible to create good local jobs for those who need them and most equitably share the benefits of transitioning away from fossil fuels across all communities.

BEI views cities as agents of change that can accelerate this transition by launching innovative policies and de-risking approaches for others at the state, regional, and federal levels of government. BEI was founded in 2018 and now assists twelve leading cities across the country. BEI supports the vision of equitable and scalable building electrification by working directly with these cities across three strategic priorities:

1. Local and Regional Market Development

Market development activities create customer demand while also building local and regional supply chains. The simultaneous focus on demand and supply is key since increased customer demand must be met with a sufficient supply of trained contractors to drive down costs and ensure high-quality installations of the systems. At the same time, engaging and training contractors will be successful only if there is sufficient customer demand to justify the time and new skill development that will be required.

2. State and National Partnerships and Policy Change

To enable a widescale transition, cities cannot simply act on their own and will need to partner with states, utilities, the private sector, community-based organizations (CBOs), and many others. Partnering with states and utilities will be particularly critical since states typically regulate energy infrastructure and utilities will need to change their operations and business models to support building electrification. Over the long term, these partnerships will help lay the foundation for more ambitious regional and national policies that will be necessary for transitioning the entire economy off fossil fuels.

3. Enabling an Equitable Transition

An equitable transition will require major investments into low-income communities and communities of color to help mitigate past harms and to ensure equitable access to the benefits of building electrification. This focus is even more critical in light of the public health and economic crises resulting from COVID-19, which has disproportionately impacted these communities. Key opportunities for equitable building electrification include co-creating solutions with frontline communities, prioritizing investments based on public health and safety needs, investing in workforce development and improving job quality, and ensuring strategies reduce housing and energy costs and prevent displacement of low-income people and people of color.

Since 2018, BEI’s cities have been setting the standard for equitable building electrification across the country. In 2019, Berkeley, California enacted the first law in the nation eliminating fossil fuels in new construction, which lowers the costs of both housing construction and gas infrastructure maintenance. Dozens of cities in California and elsewhere have since followed suit and enacted similar codes. New York City enacted a policy in 2019 that requires GHG emissions reductions from large existing buildings that will accelerate electrification over time, which dozens of other cities are now seeking to replicate. And Washington, D.C. recently eliminated all incentives for gas appliances from the DC Sustainable Energy Utility, which other states and utilities will hopefully soon pursue.

More details on the progress of two additional BEI cities—Salt Lake City, Utah and Burlington, Vermont—are highlighted in the case studies below.

Case Study: Salt Lake City, Utah

Salt Lake City has long been a leader in environmental action and is committed to achieving an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2040. The city is also experiencing rapid growth as it attracts new residents and businesses from across the U.S., which presents both opportunities and challenges for reducing building emissions. Many of Salt Lake City’s efforts to date have focused on improving air quality while also reducing GHG emissions since the region’s rapid growth combined with its geography presents significant air quality challenges.

Fire Station No. 14 in Salt Lake City, Utah uses high-efficiency design, on-site solar, and ground-source heat pumps to cut energy bills and pollution. © Blalock and Partners

To help counteract these issues, the city has moved forward with a number of innovative new policies and programs. Since 2013, Salt Lake City has required net-zero carbon emissions in newly constructed municipal buildings, thereby leading by example in its own facilities. The city also led successful efforts to enact the Community Renewable Energy Act of 2019, which is statewide legislation that sets Salt Lake City and other municipalities in Utah on course to achieve net-100% renewable electricity by 2030. To continue its progress, Salt Lake City is now focused on electrifying buildings to take full advantage of its increasingly clean electricity.

Analysis of local conditions in the region found that all-electric new residential construction is less costly to build and can be more affordable to operate— one reason why a growing number of local developers in Salt Lake City are already building all-electric. These insights are informing the efforts of the City and several partners to evaluate state code opportunities that ensure new buildings in Utah are built “Electric Ready,” with the necessary wiring and electrical capacity for all-electric appliances and electric vehicle charging. Salt Lake City is also now exploring opportunities to partner with its electric utility, Rocky Mountain Power, as part of its transition to a more electrified community.

Case Study: Burlington, Vermont

In 2014, Burlington became the first city in the country to source 100% of its electricity from renewable sources. Following that accomplishment, Burlington is now committed to achieving net-zero energy by 2030 in the building and transportation sectors.

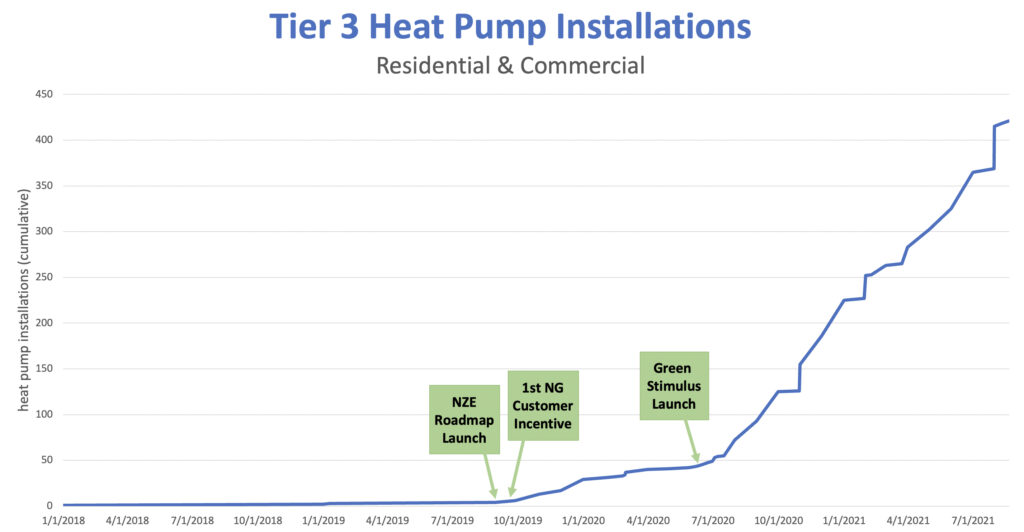

Because Burlington has a very cold climate, wintertime heating in buildings is a very large source of the city’s GHG emissions, and roughly 95% of buildings use natural gas for heating and hot water. In 2019, the Burlington Electric Department (BED) launched a cold-climate heat pump rebate program to help reduce these emissions, which includes a combination of weatherization services and installations of high-efficiency electric heat pumps. BED prioritizes low- and middle-income customers for this program by providing enhanced incentives so they better afford energy-saving heat pumps, which provide both heating and cooling, a key benefit as Burlington experiences hotter summers. In 2020, BED expanded this program under a “Green Stimulus” to help counterbalance the economic impacts of COVID-19, which dramatically increased customer uptake of heat pumps in Burlington—in total, more than 1,000 customers have now installed heat pumps using BED incentives.

Burlington has seen exponential growth in the installation of heat pumps after offering enhanced incentives under a local Green Stimulus program. © Burlington Electric Department

BED incentives

Burlington has also pursued policies changes to accelerate building electrification. In 2020, the City updated its existing housing code to require the installation of weatherization measures in rental properties to help prepare its existing building stock for electrification. Additionally, after completing an analysis that found that all-electric buildings can be constructed at similar or lower costs to mixed fuel buildings even in its cold climate, Burlington enacted a policy in 2021 that requires all new buildings to have heating systems that can serve at least 85% of the space heating load with high-efficiency electric options, such as air source or geothermal heat pumps—which will provide a clean source of heating for these buildings even during Burlington’s coldest winter days.

Learn more: beicities.org

About the Author

Jenna Tatum, Director, founded BEI in 2018 to build an organization that advances the leadership of cities in order to accelerate an equitable transition away from fossil fuels. Prior to BEI, Jenna served in the NYC Mayor’s Office of Sustainability where she designed programs to accelerate energy upgrades in buildings and assisted with the development of the City’s building sector strategy to achieve its ambitious climate commitments. Jenna previously served in the U.S. House of Representatives and has a Master of Public Administration degree from Columbia University.

Sources

1. RMI, The Economics of Electrifying Buildings https://bit.ly/2WlKnd7

2. In New York City, for example, on-site fossil fuel use in buildings accounts for 42% of the city’s GHG emissions, which is the largest single source of citywide emissions. See New York City’s Roadmap to 80×50 https://on.nyc.gov/3mCbvQg

3. Based on average rents reported on rentjungle.com.

4. National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach: The High Cost of Housing https://bit.ly/3mHeR4B

5. Sierra Club, New Analysis: Heat Pumps Slow Climate Change in Every Corner of the Country https://bit.ly/2WkFx0d

6. See the University of Southern California’s report, The Climate Gap https://bit.ly/38ntSQl

7. American Public Health Association, Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status https://bit.ly/3kt0Aph

8. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2014 National Emissions Inventory Report https://bit.ly/3BfYuzT

9. California Energy Commission, Emissions, Indoor Air Quality Impacts, and Mitigation of Air Pollutants from Natural Gas Appliances https://bit.ly/3znyL7Z

10. Over the past two decades, there were more than 640 gas distribution accidents, resulting in 221 fatalities across the U.S. https://reut.rs/3jiJv1L

11. The National Fire Protection Association estimates that gas use in the home is responsible for nearly 8,000 residential house fires—over half of the total—in the U.S. every year https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research